← go back to Part I: On declining progress

A history of work, automation, fear and the struggle for labor rights

The narrative that machines will take over our jobs has not only been around for years but for generations now. Louis Anslow wrote an investigative article about this topic. The first instances where machines were supposed to take over our work date back as far as 1811. Back then it were the Luddites who warned of the dangers of technology and automation. Certainly new technology can be very disruptive in a specific fields and right now were are starting to see this with generative AI in certain tech and creative fields. On the flip side, a massive increase in automated productivity could also mean we can all live more comfortably. But that rarely happens automatically. In fact, John Stuart Mill noticed that in his day of very rapid industrialization, the 19th century, it was questionable if machines had reduced toil at all1. If only those who became technologically unemployed owned enough of the company stocks where they worked. Then they could enjoy their own unemployment. And the reason that not they but a select group of speculators should profit from technological progress is really not that obvious.

There were points in history where a synergy between innovation and social struggles did result in a positive surge in material wealth and living standards for large sections of the population. Fordism is a good example. Named after the Ford factories that were exemplary of the phenomenon. Fordism strongly improved manufacturing and assembly line efficiency through standardization, automation and mass production. This increased production capacity to such a degree that workers could now buy the cars they were producing, often for the first time. But that is not the whole story of how we got there. These improved conditions were also the result of a bargain between politicized labor movements and owners of factories: reasonable living conditions in return for some peace from workers who were organized, radical and sometimes even militarized back then2. It is almost forgotten history but worker rights were also earned through worker uprisings throughout the 19th and 20th century. Things we take for granted, like an eight-hour workday, were sometimes even earned through bloodshed, which in several cases almost led to total revolutions3. Besides, Ford realized that reasonable wages also increased demand for his own products, which could now be utilized by the superior manufacturing process. However, when it comes to the type of automation where workers just become redundant there seems to be little room for negotiations. Automation is thus presented as a threat to workers and beneficial to capitalist. Still, this is not necessarily true precisely because, in the end, one does need demand4. In fact, it can be argued that, in the long run, automation and endlessly accumulating more profit, due to cutting labor costs, can be problematic for capitalists and the capitalist system itself. Also it has been suggested that - perhaps because of this - we can actually automate a lot more jobs than we actually do already56. The precise mechanisms and technicalities are still debated 7. However, one idea is that automation, or new technologies in general, increase productivity and reduce production costs but that this competitive advantage has to be exploited as soon as possible. Before the competition also uses the same or even better technologies for less investments. Moreover, machines are still tools without desires that cannot come into being without extracting value out of labor at some point, nor does it generally consume the products it produces; which brings us back the demand problem once again8. Could it be that these systemic contradictions in combination with bad policies are preventing us from reaping the benefits of our technologic innovations? In the 20th century we seemed on the right track with technological progress leading to less toil and better living conditions rapidly. For John Maynard Keynes - who shaped much of the 20th century economy – the rapid progress he witnessed was a reason to believe that these trends would continue. He famously stated that the ever improving social conditions and “technological unemployment” would result in a 15 hour work week by the year 20309. Another intellectual giant, Bertrand Russell, observed that the British wartime economy could easily sustain or even increase production with a fraction of the labor capacity10. So it is obvious, he argued, that within a few years everyone can simply work half days. Due to the lockdowns around 2020 we arguably saw a similar phenomenon again. In fact, the economy seemingly boomed as long central banks kept pushing money into the economy. Although we also saw inflation afterwards, we have to remember that we are limited by resources, not abstract finance. Still, it seems that in our modern contemporary economy sentiments and “trust” are a big part of what the actual outcomes are in the physical world. So perhaps, then, old paradigms and dogmas prevent us from doing better.

They took our jobs?! Old work paradigms and the last man

First, let us get real here. Many people are not actually afraid to lose their jobs, they are mostly afraid to lose their livelihood. Of course, in many cases people may also find meaning and status in their work and a few of us might even be lucky enough to really see it as their calling. Such people often do not see putting 60 hours a week into that particular calling as toil in the first place. But for most people, in the end, work is simply a way to survive. Many of us work on meaningful things on top of mandatory labor. Who would really mind if AI could reduce work time so we could spend more time on family and creative endeavors? Also the suggestion that people would be idle and lazy is not what was found in experiments. Perhaps more serious is the danger of an existential crisis if, as Douglas Hofstadter argued, AI could also take over work that is considered deeply human, like art. Then again, the invention of the photo camera was expected to make art worthless, yet the opposite happened. This is because, as Walter Benjamin proposed, original Artwork became extremely valuable because of its perceived human uniqueness which cannot be copied11. Apparently the value of things, and therefore also the value of work, in relation to those things, is subjective. It is all in our heads, we have to believe in it.

Dreams of how living conditions could be a lot better were plentiful in literature of 19th and 20th century. We find this in early SF-writers like H.G. Wells, Jules Verne and very notably Edward Bellamy and William Morris. Revolutionary ideas about sustainable, automated, post-scarcity and post-work societies were common science fiction and futurology ideas, very often set around the year 200012. Not to forget the ideas of the 60s counter culture. For example, Guy Debord and other Situationists who openly argued for a workless Utopia. It was not a dirty word, nor overly utopian. And why would it? The rate at which things were changing gave hope for a better world. With a few exceptions, In the 21st century it seems we let this dream go. In that sense, Fukuyama’s famous cliché “end of history”13 proclamation can be read as a dark warning just as easily as a celebration. More so because, unlike Nietzsche’s proclamation that God was dead, Fukuyama does not really provide much of an existential alternative to the Nietzchean “last Man” that would be roaming the geriatric boring dystopia of the 21st century. The last man is perhaps not the result of a lack of military conflict or mandatory work but a lack of dreams, creativity, and a sense of responsibility and purpose. We even see that utopian SF-shows like Star Trek have now turned dark, dumbed down and less hopeful in tune with our outlook of the 21st century. We cannot imagine things could be different, even though so many feel something is not quite right.

Yes they took our jobs! And produced a bunch of fake ones

And here we come to a paradigm shift that could explain a big part of what is not quite right with regard to work and automation. A paradigm shift that claims that for many of us, our work might actually already be partly or entirely redundant. A scenario of a redundant work force may have occurred a long time ago and yet unemployment is relatively low in postindustrial societies. How? This brings us back to David Graeber14. He stirred up quite some controversy with the idea that many people might already be working for the sake of it in those postindustrial societies. I am talking, of course, about the Bullshit (BS) Job. Graeber argues that, in many jobs, on average, you already have a 15 hour work week as Keynes predicted. It is just this that you fill the rest with nonsense, while those who do essential work, do overtime. Some jobs would even be entirely fake (the actual definition of a BS job). And some jobs that might be useful in themselves could still be in service of a BS industry. Examples of jobs with a high degree of nonsense are the bureaucratic managerial jobs full of meetings, seminars, auditing, self-auditing, auditing the audits, conferences and documenting all of this into SMART and lean formulated mission statement reports, no one ever really reads15. Especially these relatively well-paying bureaucratic jobs have grown tremendously16, whereas essential work is often understaffed and not well compensated. Indeed, some economists have shown that the amount of compensation for work also does not make rational economic sense or is even almost inversely proportional to its usefulness17.

These phenomena in the workplace can be traced back to the New Public Management philosophy and the phenomenon known as Market Fundamentalism. Both became prominent in the 80s and 90s. The underlying models of Game Theory and Rational Choice Theory18 assumed that all of society, public and private, had to be run like a (quasi-)market in which rational actors would all pursue their self-interest. This was supposed to encode everyone’s desires into society in a way democracy could never do. But since not everything is naturally a competitive market, it also produced the need to introduce all kinds of metrics to continuously measure and assess everyone and everything with audits and targets. Market fundamentalism was meant to increase efficiency and reduce bureaucracy. However, to make it function a huge managerial bureaucracy of managers and administrators was actually required. In health care, for example.

Needless to say, the methods did not work, failures are everywhere19. The fundamental psychological assumptions seem wrong – people are generally not simply self-interested rational actors20. Also, it often forces things to be quantified that are not really quantifiable. Moreover, people have a tendency to focus on unimportant statistics instead of actual performance and we even constantly see that organizations are trying to ‘game the system’. After all, judgement is based on the statistics to look good, not that things actually work well.

The futurologists and SF writers like Asimov and Toffler predicted that technological progress would produce a demand for engineering and technological specialists and that everyone else would be priced out of the market. But what we got instead was four new layers of managers. Yes, we do have way more programmers but not nearly as much as the managerial legions of consultants, the growth of which really exploded after the 90s as well. Yet, when budget cuts are required it often falls on the shoulders of the people actually doing the work. This is also because those tasked with efficiency are typically ‘finance and management people’ who sometimes do not understand technological long term predictors for success, such as innovation21. The entire ‘knowledge economy’ might as well be a lie. The movie Office Space shows a work floor perspective of this managerial lunacy quite brilliantly. Clearly something is wrong.

There are quite some reasons why BS jobs might exist besides the need for a managerial bureaucracy. To investors it looks good if your organization has many ‘highly qualified’ auditing task masters or flunkies22 for window dressing. You signal that your organization must be pretty complex and important if so many bureaucrats are required and so many people answer to you. In fact, a trivial correlation between the number of people that answers to you and wage has been suggested23. Also, having a bunch of loyal well-paid upper middle class clerks to do your bidding might be convenient for upper management and elites in general. And the gloomiest explanation that Graeber provides is that, after the 60s counter culture, the upper classes just wanted to prevent that people got too much time on their hands. But let us not forget once again: workers consume and machines do not.

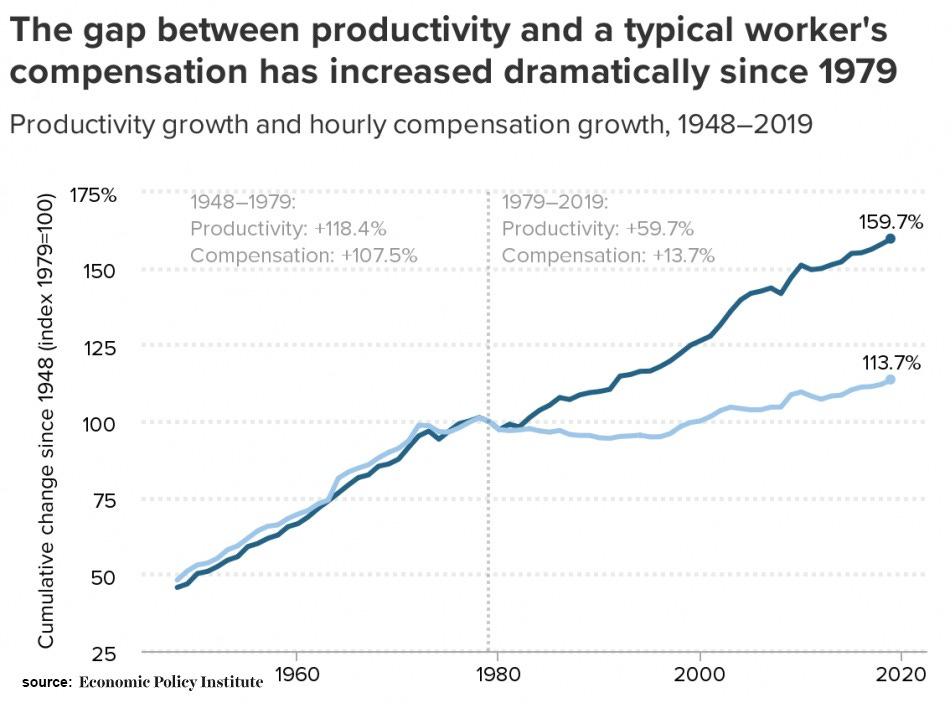

The BS job seems to make no sense in a market economy. It stands in contrast to the desire to cut labor costs, for example, as a result of technological unemployment and offshoring. However, money and cheap credit is (over)abundant in the ‘financialized’ economy - especially since the massive ‘rescue operating’ following the 2008 crisis - speculators basically sit on ever increasing piles of public money they either got directly or through the backdoor using monetary tools like quantitative easing. In fact, economist Paul Krugman has suggested that pretty much all economic expansion since the 80s has been a bubble. This might be why unemployment always remained low in the aggregate. In the end either the managerial bureaucracy provides new (BS) jobs or sectors like the gig economy provides new precarious jobs. But welfare programs have to remain limited. It is not all black and white of course but the previous observations by Bertrand Russell, Keynes, as well as the lockdowns gave ample indication that Graeber’s thesis could actually be true. If we finally look at the gap between productivity and compensation it is also clear why things could have been different. Since the late 70s the fruits of rising productivity have been eaten by capital accumulation and speculative practices in the financialized sector. That could have also been used to make the lives of many people less precarious with no obvious cost to productivity.

→ Continue to PART III: On failed and dogmatic economics

John Stuart Mill (1849). “Principles of political economy, with some of their applications to social philosophy” Book IV, Chapter VI, Section 5 p. 314

Also the idea that one day communism might offer an alternative to workers was secretly feared.

Revolutions of 1848 (age of revolutions) swept through Europe and beyond, often had strong socialist characteristics and lasting impacts. The failed The German revolution after WW1 (1918-1919), the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 in the US that led to the progressive era etc. Many radicals noted that there were so many widespread strikes after the destruction of world war I that world revolution actually looked inevitable and upper-classes everywhere were becoming quite nervous.

Karl Marx (1867) “Das Kapital”. Marx’s Theory of Value: Chapter 15 section 1. Marx starts by quoting John Stuart Mill and his Principles of Political Economy about machines not reducing toil. Marx continues to explain why machines do not create surplus value.

David Graeber (2012). “Of Flying Cars and the Declining Rate of Profit.” The Baffler No. 19 pp. 66-84

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation presented interesting research showing a positive correlation between higher wages and the adoption of robots/automation. However, they also found that some countries lagged in the adopting automation for reasons that could not be easily explained. https://itif.org/publications/2021/01/25/robots-and-international-economic-development/

For example, Matthijs Krul (2012). Steve Keen’s Critique of Marx’s Theory of Value: A Rejoinder

Ultimately everything is energy. It seems that human consumers consume energy that have, in them, a lot of surplus, speculative and ‘commodity fetish’ value. Machines only consume energy in its most essential form. Unless, perhaps, AI becomes part of the evolutionary life chain and has desires too. This is farfetched and might also show the tendency to anthropomorphize.

John Maynard Keynes (1930). Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren

Bertrand Russell (1935). In Praise of Idleness and Other Essays

Walter Benjamin (1936). “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”

Examples, e.g. Edward Bellamy (1888). “Looking Backward”, William Morris (1890). “News from Nowhere” HG Wells (1914). “A Modern Utopia”, “The World Set Free”. Though not Utopian the strangely accurate predictions of Jules Verne’s 1863 book “Paris in the 20th century” should also be mentioned.

Francis Fukuyama (1992). “The End of History and the Last Man”

David Graeber (2018). “Bullshit Jobs: A Theory”

Mark Fischer (2009). “Capitalist Realism”, see chapter “All that is solid melts into PR: Market Stalinism and

bureaucratic anti-production” for examples of bureaucratization in the (post)modern workspace.

For example, the Bureau of Labor Statistics; NCHS; Himmelstein/Woolhandler analysis of CPS shows an almost 3500% increase of administrative personnel in hospitals since the 80s, whereas the number of physicians only increased very slightly compared to this explosion of bureaucrats.

David Graeber (2018). “Bullshit Jobs” pp. 242-243. Data is shown from economists Benjamin B. Lockwood, Charles G. Nathanson, E. Glen Weyl from the paper “Taxation and the Allocation of Talent ”. The correlation between the value of work added and salary in return was found to be controversial. In fact, it was almost inversely proportional.

Mathematician John Nash played an important role, as well as Kenneth Arrow and Gérard Debreu

Michael Power in his book "The Audit Society" showed how profession judgement is distorted by the constant focus on audits.

Among others Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (Prospect Theory) showed that the idea of rational self-interested actors looking for gains is wrong.

In fact, a common practice conducted by so-called equity funds is to buy a company, stripping it from personnel costs so it seems more efficient and profitable while the company actually becomes unproductive and loses the ability to innovate.

These were terms introduced by David Graeber (mostly in “Bullshit Jobs”)

Blair Fix (2020). “How the rich are different: hierarchical power as the basis of income size and class”. Journal of Computational Social Science.