← Go back to PART III: On failed and dogmatic economics

False needs, AI, prosumers and influencers

Those who defend present-day consumer society maintain that the modern consumer is exceedingly needy and that the system merely accommodates those needs1. This neediness should be one of the most important traits of the so-called contemporary prosumer. Prosumer is a term coined by “Future Shock” Toffler, who predicted the rise of increasingly conscious and participatory consumers. Online the consumer indeed participates, consumes and feeds the algorithm. Even if you are not consciously participating your digital footprint is somehow turned into valuable capital. So this blurring between consumer and producer actually seems to make some sense; it was certainly one of Toffler’s more profound predictions. Nevertheless, if innovation is not what it seems (see PART I) and the economy is not what is seems to be (see PART III), maybe that desire for ever more consumerism is also not what it seems to be either.

There is certainly a lot to this hypothesis. It is well-documented that in the 19th and especially the early 20th century, many tycoons became concerned - not so much with producing enough products for everyone’s needs - but how to sell products beyond those needs. Sure, sometimes you may not know you want something until someone offers it. However, needless to say, the capitalist world became increasingly focused on producing false needs using advertisement, marketing strategies, and even manipulation. These efforts continue to this day in extreme forms. Early developments in advertisement and consumerism started in the 1920s, ‘propaganda specialist’ Edward Bernays – who was also Freud’s nephew – played a central role. He understood that unconscious mechanisms, herd psychology and appeal to authority can be utilized to make consumers desire all sorts of things to keep demand high2. This is where the term PR (public relations, instead of propaganda) originates and it became the modus operandi of the ‘capitalist’ West to pursue both corporate as well as (geo)political interests, which are often increasingly interconnected3. As Lehman Brothers banker Paul Mazur put it in 1927: “We must shift America from a needs- to a desires-culture. (..) Man's desires must overshadow his needs.”4

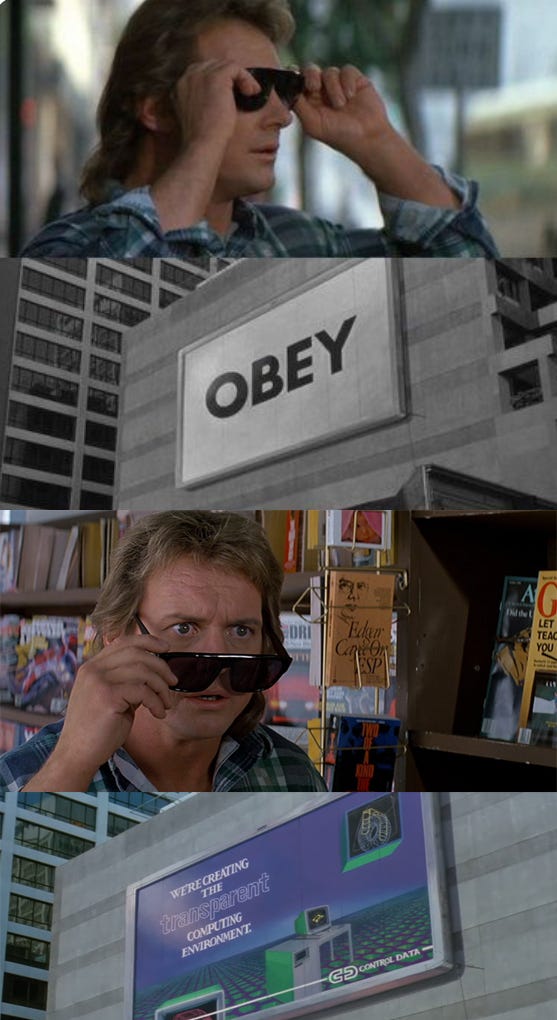

An innocent example of a false need is a senseless fashion trend. Less innocent is promoting women to smoke by associating smoking with a liberal independent identity, which was a marketing strategy suggested by Bernays. But there are also other ways to keep demand artificially high that became common, such as covertly designing things not to last (planned obsolescence), which will force people to spend more on repairing, healing or replacing the product. A famous example is the original incandescent light bulb, designed to only work for about a 1000 hours. A recent trend to keep demand high is to rent things out and force consumers to take subscriptions instead of owning things. Although from an environmental perspective this can be sold as something positive, it is also clear that making products and services practically worse can have a positive impact on profits and therefore also on metrics like GDP-growth - which can, in turn, be used to paint an overall positive PR-picture. In recent decades PR has grown into a highly sophisticated theater of spectacles to distract, divide, uphold demand and manufacture consent5 by incorporating the political, the social and even the spiritual6. The movie They Live from 1988 - today commonly used in memes - shows early examples of the absurdity quite well. The protagonist wears glasses that show him the actual authoritarian subliminal messaging behind advertisement in the public space - very different from what the advertisement literally says. Signs with ads suddenly say things like “Consume” and “OBEY” after the protagonist wears the glasses.

Today it goes even further, people now actually identify with products, brands and ads – sometimes they even defend these brands as if it is part of their tribal identity. The prosumer thus becomes a (re)producer of PR hypes and advertisement as well. This seems to be accomplished by effectively appealing to deep-seated tribal and hierarchical instincts, transferring the messaging with reproducible memes and amplifying its reach through social media, in some cases in combination with gamification. PR thus becomes a self-amplifying feedback loop. Indeed, with this type of consumption you buy into a new ‘self’, a new ego construction, all the time7. People want to drive EVs but for some it is even more important to belong to a certain climate conscious tribe8. Similarly, because of the political associations of a CEO, owners of EVs suddenly feel ashamed of their car. Clearly it is not about the product. We see big companies such as banks, consultancy firms and even military “defense” contractors displaying certain flags, banners and slogans to signal which of the current, constantly changing, causes they support or follow. But behind the façade we see that there are often interwoven commercial and political interests. In fact, after the 2024 election in the US we see how ethically flexible companies really are when it comes to these causes. Yet, many people willfully copy the quickly changing trends. In many cases we also see anti-system and anti-status quo activism itself being co-opted. The anti-capitalist parody on the cup of your favorite hip coffee place is actually part of the product that is your overpriced coffee. It should be no surprise then that the aforementioned slogan “OBEY”, from the movie They Live, has actually been turned into the name of a real fashion brand with an activist inclination. All of this is herd behavior on dissociative steroids. Other striking examples of contemporary PR and advertisement are websites of expensive outdoor brands full of stories about self-actualization and semi-spiritual journeys that have basically nothing to do with the actual product. We see these phenomena in the financial world too, for example, in ESGs (Environmental, Social and Governance) – a metric to encourage investment in responsible companies. And of course, the subsequent abandonment of these causes with changing political winds by the same financial institutes speaks volumes. Even if these initiatives are not born out of opportunism, companies have no choice but to compete in favor of the shareholders and government privileges, so hypocrisy is intrinsic to the system. Another common example of this is the phenomenon where ‘responsible’ companies, supporting all kinds of progressive goals, still produce their products in sweatshops. Not to mention the phenomenon of greenwashing.

Even presidents are now elected using similar marketing and mass psychology tactics, sometimes with the help of specialized firms9. Moreover, consultancy firms are known to be deeply involved with political parties, carefully constructing hypes, tribes and outrage to attract voters as if they were consumers. Once the politician is in power, some journalists have suggested that these companies seem to be receiving privileges in return10. Big Tech is no stranger to PR either, and not just as a service but also for themselves. After all, a lot of big tech runs on billions of venture capital and speculative stocks (e.g. high price to earning ratios), supported by loose monetary policy. That means that having a good story is paramount. And this could explain the fear around AI as well. As professor in AI Melanie Mitchell states:

The “unexplainable” narrative gives rise to fear, and it has been argued that, to a degree, public fear of AI is actually useful for the tech companies selling it, since the flip-side of the fear is the belief that these systems are truly powerful and big companies would be foolish not to adopt them.

Occasionally very interesting innovations come out of venture capital or other big investment methods. In fact, the way our economy is structured right now, it is probably one of the few ways that many tech companies can provide the innovations we do enjoy, often seemingly for free. However, in many other cases “the next big thing” appears to be yet another unprofitable ‘Uber clone’. Moreover, some of the famous big tech products were not really something exceptionally challenging or even original from a technological perspective11. Similarly, some of the current tech billionaires arguably pale in comparison to the Bell Labs pioneers who laid the foundation of the digital revolution, most of whom never got particularly rich. That founders of big tech companies are self-made geniuses can be part of the marketing. Even their net worth might be used as advertisement to show how great the company is doing. Who is able to tell when the hype is real? The debacle of the completely fake ‘innovative’ blood testing company Theranos suggests that highly respected investors cannot really tell the difference either. Crypto exchange FTX was another example. Sure, these are extreme examples but it also shows that the entire economy might as well be overvalued and overhyped12. Although it is safe to say that AI will have impact because of the technology itself, in many other cases the PR is all there is. And even if an online conglomerate is dominating a market, they often produce revenue by, again, relying on behavioral psychology. For example, algorithms controlling people’s shopping behavior, exciting tribalism and outrage and capitalizing on it. Making profits is not even that important, the possession or anticipated acquisition of user data, which can be turned into (ad) revenue, is enough for speculators. Or even just the expectation that a company will one day dominate a market. These speculators sit on piles of “too big to fail” excess liquidity since 2008 anyway. This is another reason why PR is so important; we all have to subsidize this model. As Varoufakis argues, the world of big tech hardly functions like capitalism at all, many big tech companies act as fiefdoms between the actual capitalists and consumers now13. It should be clear that all of this goes much further than pandering to needy consumers.

But can it last? For the time being, a big reason why this economy keeps working is speculation. Financial bubbles seem to be intrinsic to the system14. In such a world, it makes sense that investors simply need to put their money where other investors put their money to keep their relative wealth15 The next fuzz, the next and best PR-hype is all that still matters, it has this Ponzi-like tendency. This also produces a system that drifts further and further from being meritocratic and hungry for actual innovation, and this affects all of society. With all the TikTok influencers, scammers, questionable Instagram millionaires and talentless ‘reality’ icons, it certainly seems that our economy is channeling more and more energy into fake attention seeking nonsense, false needs and the exploitation of the vulnerable than ever before. The prosumer with an attention span of only a few minutes seems defenseless against this new culture industry. But on the other hand, we might also simply be looking at a system that is spinning out of control.

Escape from postmodern purgatory, start dreaming again

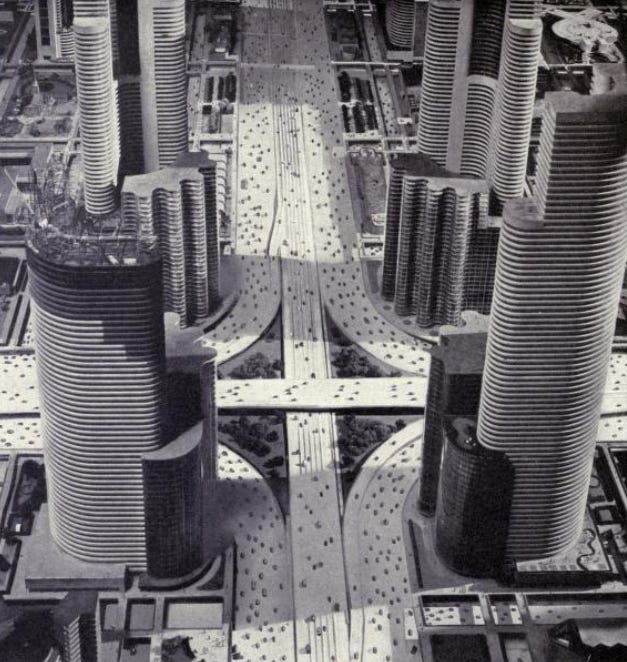

Since the 19th century, the World’s Fair Universal Exhibitions have celebrated technological and industrial progress, promoting innovation as a path towards a better tomorrow. Especially after the great depression the promise of welfare and comfort for the masses, brought about by innovation and solid industrial policies, were common themes of the Universal expos. Names such as “A Century of Progress”, for the 1933 International Expo in Chicago, or “The World of Tomorrow” for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, capture these sentiments well. These two exhibition in particular showcased visions such as futuristic car-centric landscapes, as exemplified by the famous Futurama exhibit. Of course, looking through today’s eyes such visions of progress can easily be seen as problematic. And we now know that the obvious consumerist impulses were not always genuinely positive to begin with.

In fact, this awareness was already present during the 60s, although the 1962 Seattle world’s fair named “Living in the Space Age”, still had a technological-utopian inclination. Clearly impacted by the space race, it perhaps reflected the kind of social techno-optimism also seen in the original Star Trek series. Nevertheless, the 1960s were still clearly marked by a widespread youth revolt against consumerism, corporate life, the Vietnam war and the status quo in general. Perhaps because of these social pressures, the second (unofficial) New York World's Fair in 1964 chose the slogan of “peace through understanding” instead of an emphasis on technology. From this point on, themes of the world’s fairs started to deviate from its original technological utopianism altogether. This can also be understood considering the impact of the horrors of world war II as well as the cold war anxiety. Moreover, not only consumerism but also the environmental impact of technology became a major point of discussion during this period - and it would remain an important concern for the 60s generation and their children. Despite all this, the 60s were perhaps the last decade where utopianism - or the idea that we can do better at all - was still really alive. After this, visions of the future turn darker. The utopianism of the 60s was probably also a good vibration produced by the postwar economic boom, which was characterized - not only by years of high economic growth - but also a high degree of equality, cheap and accessible high quality education, strong welfare states, as well as very fast technological developments during the space race that were not necessarily consumerist in nature. As explained in PART III, most of these things significantly changed in the late 70s: the economy essentially took a much more reactionary turn. However, this new economic rhetoric - further normalized in the 80s - seemed quite compatible with the individualism, self-expression and anti-government sentiments of ‘generation 68’16. The maturing - and by now often affluent - former hippies and beatniks still saw labor unions, the state and middle class life as something dusty and old, while the fiscally conservative thinkers did not have a lot of problems with the cultural left. Also typical changes of the time, like globalism, are easy to sell as a progressive cosmopolitan effort instead of a ploy to reduce labor costs or even a ploy to sidestep democracy17. So it can be argued that during this new anti-consumerist environment, the 60s counter culture itself became essentially commodified, which actually reignited a massive surge in consumerism18. Nowhere was this merging of global capitalism and the, sort of, psychedelic, progressive, anarchist and libertarian 60s subculture more obvious than in cyberdelic Silicon Valley. Silicon Valley, as we know it, really developed between the 70s and 2000, essentially leading the digital revolution. However, that revolution was the inheritor of the privileges and freedom that the 60s generation enjoyed, namely, that high quality and affordable education, the huge cold war investments in the tech sector (e.g. DARPA), as well as the freedom to combine this with the visions of the 60s counter culture. But things slowly but surely changed after the 80s and 90s as nihilistic consumerist impulses, globalism and market fundamentalism became more dominant. Especially after the financial crisis of 2008 a tipping point seems to have been reached19. It is from this period that we really see the, predominantly online, so-called culture war rising to prominence as well. While big tech and the online world were initially often seen as hotbeds of progressive culture based on the 60s counter culture - albeit within the hyper capitalist status quo - we now saw a more reactionary counter culture developing in cyberspace too. Perhaps it had been lurking in the shadows, perhaps it was a reaction to the wreckage that globalism and the 2008 crisis left in some places, possibly it was also embraced as a method to sow division and distract from more serious economic problems. Probably a bit of everything20. Although it also remains hard to really characterize and pin down these cultural phenomena, much of it is ironic or ambiguous, revealing a certain cultural nihilism. It can be argued that, in the end, it is part of the same so-called postmodern culture where constantly changing smaller narratives dominate instead of any overarching narrative21. This cultural stagnation has been described as being stuck in an eternal now, with a constant tendency to recycle the past as if we suffer from a severe case of nostalgic melancholia. Take all the movie remakes and reruns, for example. As Mark Fisher22 described it

The slow cancellation of the future has been accompanied by a deflation of expectations, a retreat from the idea that culture could ever be genuinely new.

Indeed, these phenomena had been present for a few decades but during the post-2008 era it seems to peak. After the crash much of the financialized economy appeared to be somewhat of a giant lie, and so it seems the status quo withdrew behind the veil of its crony economy, managerial bureaucracies, cheap advertising and PR mechanisms even further than they already did. The system has been on life support ever since and, perhaps, this postmodern culture on steroids has to prevent us from seeing this. From this perspective it is unfortunate that after the total system collapse in 2008, the opportunity was not used to truly restructure society on a fundamental level. Although there was a noble attempt by the Occupy Wall Street movement for a while.

In the West this postmodern cultural emulsion is no longer confined to Silicon Valley and cyberspace either. A great example is the global city. Many of these gentrified big cities have - since the turn of the millennium - reinvented themselves as global hubs full of financialized (zombie) businesses, tech bro startups, pseudo-cosmopolitanism, overpaid yuppies, underpaid gig economy workers, hugely overvalued real estate, ironic pastiche art, retro fashion trends, nostalgia driven coffee shops inspired by 90s sitcom culture, and political-corporate memes in the streets disguised as progressivism. Indeed gentrification is central to this phenomenon, it usually follows a similar pattern. First, original inhabitants are pushed out by a new young creative class looking for some authenticity when, they too, increasingly have to make space for bizarre luxury apartment buildings with ironic names, and complete with indoor community spaces, where you still find advertisements everywhere. All of this amplified by international investors who sit on piles of excess liquidity. Perhaps an improvement over the urban decay that defined many Western cities in the 70s and 80s but, on the other hand, these cities now arguably lack any true authenticity, creativity, diversity and soul. They all feel exactly the same. It is a simulacrum of what the cosmopolitan city once was, sold as an expensive product. The material manifestation of the ‘everything bubble’ that seems to define the contemporary Western world as a whole.

But I like to close on a positive note. Our problems are not inevitable but largely because of our attitudes and those attitudes can be changed. One of the most powerful sentiments a status quo tries to uphold is that the masses have no power, that “There Is No Alternative”, that it does not matter who you vote for and what you think. But this is factually false, the governed always rule the government and what we believe makes all the difference of the world. We do see some sparks that things are changing. From independent podcast culture and media, decentralized technology, a new aversion towards big crony capital and bureaucracies. Perhaps even things like the psychedelic renaissance breaking through old taboos can be seen as a positive cultural shift. As we have seen for the last couple of years all of these things can also be captured by the same cultural confusion and bring negativity. Gurus are rarely what they seem. Perhaps a certain degree of alienation has to be embraced. But in the end there is at least some change and some potential. What is still missing are the narratives that are coherent, new and interesting enough to bring about enduring change. We are still distracted and divided against each other by a theater of constant outrage that seeks to prevent truly new radical narratives from forming. But if we at least boldly start dreaming again, maybe we can continue on a path of progress. By rekindling a spirit of truly innovative and radical thought, perhaps we can improve our lives in synergy with the planet. This is long overdue.

This can also be related to the idea that "supply creates its own demand" as formulated of Say's law, which was fundamental to Keynes’s criticism of classical economics.

Much of this is explained very well in Adam Curtis’s documentary “Century of the Self” (2002)

Edward Herman, Noam Chomsky (1988). “Manufacturing Consent”.

Mazur. (1927). Quote in the Harvard Business Review

Edward Herman, Noam Chomsky (1988). “Manufacturing Consent”. Corporate interest regularly coincide with geopolitical interest and coercion. Moreover, industry that seems private is subsidized, especially through defense spending.

Guy Debord. (1967) “Society of the Spectacle” thesis 17. The decline of being into having, and having into merely appearing

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (1972). Anti-Oedipus thesis. Consumer’s egos are being formed and dissolved all the time for capitalist machines to find new paths (producing new territories) for profit. They also see the “schizo”, who is unable to form a coherent ego at all, as the antidote to this.

This joke was once again not lost on Southpark (“Smug Alert!”, season 10).

A famous example of such practices is the Cambridge Analytica scandal

See, for example, the close connection between McKinsey and French president Macron. https://www.lemonde.fr/m-le-mag/article/2021/02/05/de-la-creation-d-en-marche-a-la-campagne-de-vaccination-mckinsey-un-cabinet-dans-les-pas-de-macron_6068833_4500055.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

For example, Facebook was just one of many social networks, and Reddit is just a forum with channels, similar boards have existed since the 80s.

See the concept of the “everything bubble”

Yanis Varoufakis (2023). Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism

Krugman (2013). https://archive.nytimes.com/krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/11/16/secular-stagnation-coalmines-bubbles-and-larry-summers/

Only a small fraction of capital is used for production. The rest just floats around the financial system or even just sits still.

David Harvey (2005). “A Brief History of Neoliberalism” p. 42

The Trilateral Commission published an influential report “The Crisis of Democracy” in 1975 suggesting there had occurred an “excess of democracy” during the postwar period in the West and Japan.

Fredric Jameson (1991) “Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism”

Mark Fisher (2009). “Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?”

See e.g. Curtis Yarvin, Nick Land and the Dark Enlightenment.

Mark Fisher (2014). Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures.

This peak postmodernity is, in my opinion, the world of constantly changing hypes, pastiche retro, irony, influencers, identity politics on steroids etc. Also consider that postmodernity is, in fact, a reflection of modernism. This resonates with Fredric Jameson’s (in his essay Postmodernism and Consumer Society) essence of the postmodern state: no grand narratives, pastiche, a breakdown of signifiers, being in a state of the eternal present etc. According to Jameson, postmodernity is central to the late capitalist mode of (cultural) production. In other words, postmodernism reinforces consumerist society and speculative economics. Postmodernism does not oppose the status quo, like modernism did. But can it? Many postmodern thinkers had this aim but we have not seen much of this in practice, the economic orthodoxies that occurred in the late 70s are still very dominant. After 2008 it is almost as if postmodernity was reinforced to save the status quo and their crony economic networks of power. So it is hard to see how postmodernity is revolutionary. Perhaps, on the contrary, if the materialist mode of production is actually radically altered we might see much more revolutionary movement.